Who owns the dead?

Agatha Christie, Digital Doubles, and the Future of Knowledge

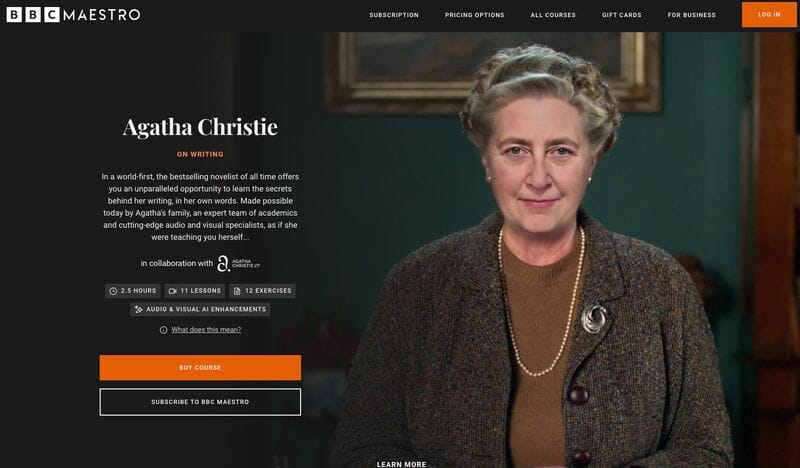

The BBC’s recent release of an Agatha Christie writing course - delivered by a digitally recreated version of the late author - marks a new frontier in digital education. Hosted on the BBC Maestro platform and developed in collaboration with the Christie estate, this project raises important questions about the ethics of digital resurrection: when it is appropriate, how it should be done, and what it means to learn from a constructed version of the past.

A Hybrid Human-AI Performance

At the heart of the project is a blend of traditional performance and synthetic media. Actress Vivien Keene provides the physical base for Christie’s likeness, selected in part through facial biometric screening. Her movements and expressions are digitally enhanced to create a version of Christie that is lifelike without plunging headfirst into the chasm of the uncanny valley.

This method - anchoring digital recreation in a live actor’s performance - is an alternative to fully synthetic avatars. The human layer potentially adds a kind of moral warmth and authenticity that pure animation typically lacks. It also invites a key question: when we watch this digital Christie, are we watching an echo, an interpretation, or something altogether new?

The answer lies, in part, in the process. The project involved over 100 professionals, including AI developers, voice engineers, scholars, and estate representatives. It took two years to complete. TWO YEARS. With the speed of developing technology, this seems like a monstrously long time. However, this can perhaps be seen not just as a sign of technical and logistical effort, but as a marker of ethical intention. Does the care and time with which something is built reflect the care with which the subject is treated? Does this make a difference to how we perceive it, its value, and authenticity?

Ethical Considerations: Four Key Dimensions

Digital resurrection is not ethically neutral. It involves recreating a person’s presence, speech, and sensibility - in some cases without their explicit consent. That makes the Christie project a useful case study to open up these issues, as the author herself obviously had zero involvement in the project.

Temporal Distance

Christie died in 1976. That distance matters. Does it grant a kind of ethical buffer: far enough for the person to be part of history, close enough for their voice to remain culturally relevant? Temporal context helps shape the tone and intent of a recreation: this is not myth-making, but education.

Permission and Partnership

The project was done with the full involvement of Agatha Christie Ltd., led by Christie’s great-grandson, James Prichard. His approval wasn’t symbolic; he was closely involved in shaping the material. That partnership matters. It distinguishes this project from exploitative uses of likeness, setting a clear standard: digital resurrection should be done with the consent of those who hold ethical and legal stewardship of a legacy. If that isn’t the case, we need to ask ourselves whether this is legal, reasonable, and ethical in whatever context the experience operates.

Fidelity to the Person’s Words

A central ethical commitment on this project was that “everything had to be in Christie’s actual words.” Scholars drew from her interviews, recordings, and writings to build the course. This implies no generative paraphrasing, no speculative additions. (Although it should be noted that there are likely ‘fillers’ and potentially some artistic licence...) If true, this decision imposes a necessary limitation - less imaginative freedom, more historical discipline. But it’s a crucial boundary. It keeps the recreation grounded in truth rather than fabrication.

Purpose

Why bring Christie back at all? Because she has something to teach? Wouldn’t other tutors be just as equipped? The reality is that people are intrigued by her as a person and as one of the most successful authors of all time. The course is meant to share her writing process, of course, but also to do that in a way that brings the students closer to the idea of the author herself. It would be interesting to see research on how much more engaged students are with this course than with identical content delivered by someone less well known.

Beyond the “How”: The “Why Now?”

This project arrives at a time when AI-generated faces and voices are proliferating. Technology is enabling experiences that might not be perfect replications, but are fast and are cheap. What distinguishes the BBC’s approach is its restraint and the significant budget and care employed. The Christie recreation required:

- Rigorous historical research

- A carefully cast and trained actor

- High-fidelity technical execution

- Ongoing consultation with estate and experts

The result is an ethically thoughtful approach - but one which might not be open to many less-well-funded organisations. And it is certainly not without ethical issues - as some public comments have shown.

Lessons for Museums and Educators

This model has implications for cultural institutions exploring similar technologies. Here are four lessons worth drawing:

- Respect must scale with innovation: Technology should extend our access to the past, not rewrite it for convenience. How can you work to ensure respect, whilst also achieving efficiency?

- Collaboration is non-negotiable: For significant projects, estate involvement isn’t a courtesy - it’s an ethical requirement. Consider who needs to be involved, why, and when. Build this into the timeline and demonstrate clearly the process when launched.

- Transparency builds trust: Audiences deserve to know what’s real, what’s simulated, and how the simulation was built. Drawing back the curtain shows respect for the audience as well as the subject.

- Purpose matters: Digital recreations need to be clear in their purpose, with honesty about why that person’s image is being used. This will help to ensure that the experience is designed properly. Consider whether using the likeness of someone who has passed is actually needed, or whether providing an interactive experience with an expert would fulfil the same purpose.

Looking Ahead

Curated historical dialogues, digital lectures from historical thinkers, or immersive museum guides - each new use must grapple with the same fundamental questions: who speaks, in whose words, and to what end?

If we are to bring the past to life, we must also remember to treat it as something worthy of reverence, not always reinvention. The BBC’s Agatha Christie is another test case in balancing technological possibility with responsibility.

With digital resurrection being firmly in the ‘now’, the BBC’s project shows how creators are seeking to honour the dead, enrich the living, and enhance learning through these techniques, with efforts being made in transparency, collaboration, and care. If this is to be the future of education, it must be built not just on data and code, but on ethics and empathy.