The Uncanny Valley: What We Know, What We Don't, and Why It Matters

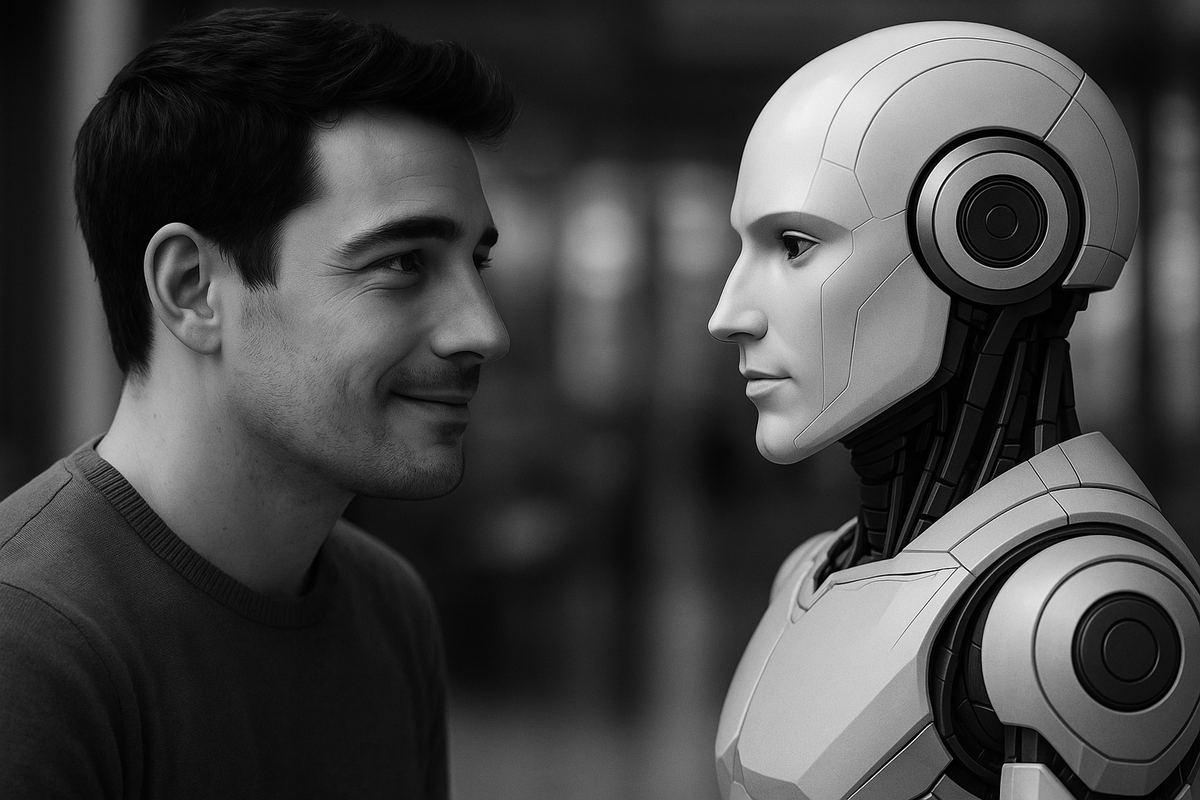

In 1970, Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori wrote a brief essay that would become one of the most cited concepts in robotics and AI. He described a curious psychological phenomenon: as robots become more human-like, our comfort with them increases - until suddenly, it doesn't. At a certain point of near-human realism, our positive feelings plummet into what Mori called the "uncanny valley."

More than 50 years later, this concept has never been more relevant. Yet despite its widespread influence, the uncanny valley remains surprisingly poorly understood. The gap between what technologists can build and understanding what humans actually want to interact with is widening. It's time we paid attention and sought to extend our knowledge about how real humans, avatars and the uncanny valley interact. Without this, mistakes will undoubtedly be made, leaving consumers, audiences, and fans unsatisfied.

The Theory: A Valley of Discomfort

The uncanny valley hypothesis is elegantly simple. Imagine a graph where the horizontal axis represents how human-like something appears, and the vertical axis represents our emotional response to it. According to Mori's theory, our affinity increases as things become more human-like - a stuffed animal is more appealing than a basic robot, a cartoon character more engaging than a simple drawing.

But this pleasant climb hits a dramatic cliff. When something appears almost human but falls just short (think wax figures, certain CGI characters - the Polar Express anyone?) our positive feelings don't just level off, they crash. We feel revulsion, eeriness, or deep discomfort. This is the uncanny valley.

The theory suggests that if designers can push through this valley to achieve perfect human realism, positive feelings return. But that's a big "if". It also assumes that perfect realism is desirable, and assumes that people are not informed that the virtual person in question is a digital construct.

The Evidence: Compelling but Inconsistent

Since Mori's original essay, researchers have attempted to validate the uncanny valley through empirical studies. The results have been... complicated.

Some studies strongly support the phenomenon. Research on AI-generated food images found that imperfect artificial food was rated as significantly more uncanny and less pleasant than either obviously artificial or highly realistic food. Studies of humanoid robots have documented measurable drops in user comfort and trust when robots appear almost-but-not-quite human.

Other research, however, has failed to find evidence of the valley effect. Some studies of AI avatars have found no descent into an uncanny valley with higher degrees of realism. Some researchers have questioned whether the effect exists at all, pointing out that Mori never provided empirical data for his original theory. What do you think? Do you have feelings or eeriness when seeing digital humans?

This inconsistency isn't necessarily a problem with the research. It might be telling us something important about the phenomenon itself. The uncanny valley may not be a simple, standard, universal human response but rather something that varies dramatically based on context, individual differences, and cultural factors.

Where the Valley Emerges: Three Frontiers

Today's uncanny valley discussions centre on three main areas where near-human AI encounters occur:

AI Avatars and Digital Humans Companies are creating increasingly realistic digital beings for customer service, marketing, and entertainment. Some aim for photorealistic human appearance. Others deliberately embrace stylized, cartoon-like designs to sidestep uncanny territory entirely. The choice isn't just aesthetic, it's psychological.

Conversational AI and Chatbots The uncanny valley isn't limited to visual appearance. As AI becomes more human-like in conversation, some users report feelings of unease when interactions feel almost-but-not-quite natural. The phenomenon may be expanding beyond sight into the realm of language and social interaction.

Humanoid Robotics Physical robots that attempt human-like appearance and movement face perhaps the greatest uncanny valley challenges. Every aspect (from facial expressions to gait to the timing of gestures) must align with human expectations, or risk triggering discomfort or even fear.

The Missing Piece: Understanding Human Nature

Here's where current discussions often go wrong. Much of the focus remains on what's technically possible: Can we make more realistic skin textures? Better lip-sync? More natural eye movements? These are engineering questions, and engineers are solving them brilliantly.

But we're asking the wrong questions first.

The critical missing element is deep understanding of human psychology and behavior. We are not rational beings making calculated decisions about digital interactions. We are animals with evolved responses to social cues, threat detection, and categorical thinking. Our brains are constantly making split-second judgments about what's safe, what's trustworthy, and what fits our mental models of the world.

When something doesn't fit - when it triggers our "this looks human but isn't quite right" alarm systems - we experience discomfort that bypasses rational thought. These responses evolved for good reasons, helping our ancestors identify the sick, the dead, or the deceptive. Knowing instinctively who we should trust was a pretty big advantage. If you weren't good at making judgements on whether someone was trustworthy, you might not get to pass down your genes.

The Open Questions

Understanding the uncanny valley requires exploring questions that research has really just scratched the surface of:

Age and Development: Do children, teenagers, and adults experience uncanny valley effects differently? Younger generations have grown up with CGI, video games, and digital avatars. Are they less susceptible to uncanny valley responses, or do these feelings transcend generational experience? Interestingly there is some evidence that younger people are more susceptible to the uncanny valley.

Gender and Individual Differences: Preliminary research suggests women might be more sensitive to uncanny valley effects than men, but the evidence is limited and sometimes conflicting. How do personality traits, cultural background, and individual psychological differences shape our responses to near-human entities?

Context and Expectation: Does the setting matter? Are we more tolerant of slightly "off" digital humans in a video game than in a customer service interaction? How do our expectations going into an encounter shape our emotional responses? Does it matter what service or product the experience relates to? Personally, and from my experience, there are some important differences here.

The Movement Factor: Mori suggested that movement amplifies uncanny valley effects, but this remains poorly understood. How do gait, gesture timing, and micro-expressions contribute to feelings of uncanniness?

Cultural Variation: Most uncanny valley research has been conducted in Western contexts. Do these responses vary across cultures with different relationships to technology, different aesthetic traditions, or different concepts of human identity?

Authenticity: Humans are fundamentally interested in the lives of other humans. Real, living, breathing people. Authenticity, authentic media, trust and ethics will all play a part in how customers and audiences feel about digital media and experiences. How will real media be interlaced with synthetic media?

Why This Matters Now

Technology companies are making big bets on digital humans, AI assistants, and humanoid robots. They're designing interfaces, planning user experiences, and setting interaction paradigms. This is fantastic and exciting work, but we need to be aware that there is much work to be done on understanding human psychology and the uncanny valley. This work and understanding needs to be built in tandem with the technology, with an awareness of the importance of maintaining authentic content and human value, and a conscious realisation of how much we don’t know.

A continued knowledge gap has real consequences. Poor AI design can make users uncomfortable, reduce trust in technology, and limit adoption of potentially beneficial innovations.

We're at a critical juncture. The technology to create convincingly human-like digital beings is advancing rapidly, but our understanding of human responses to these beings is lagging behind. Unless we catch up - unless we really understand how humans will interact with digital beings, how comfortable they'll feel, and why - companies will continue making expensive mistakes based on technical capability rather than human need.

The uncanny valley isn't just an interesting psychological curiosity. It's a fundamental challenge in human-computer interaction that demands serious research, careful consideration, and honest acknowledgment of what we don't yet know. We need to be excited about what is possible technically, but deeply appreciating that human authenticity, real lived experiences and shared stories bring beautiful value that can’t be replaced by a digital being.

The valley is real, even if we don't fully understand its boundaries. And if we want to build technology that truly serves humans, we need to map that territory with the same precision we apply to the technology itself.

The questions raised by the uncanny valley touch on fundamental aspects of human nature, perception, and social interaction. As we continue to blur the lines between human and artificial, understanding these responses becomes not just academically interesting, but practically essential. Uncanny-ai.com will explore these topics and developing research.